In the Moment:

Michael Frye's Landscape Photography Blog

by Michael Frye | Aug 12, 2010 | Critiques

“McGee Creek” by Joe Lemm

This week’s photograph was made by Joe Lemm near McGee Creek, on the eastern side of my home mountain range, the Sierra Nevada. By having his image chosen for this critique Joe will receive a free 16×20 matted print from Aspen Creek Photo. If you’d like your images considered for future critiques you can upload them to theFlickr group I created for this purpose.

This is a beautiful mountain scene, with a nice juxtaposition between flowers and distant peaks. The colors are harmonious and pleasing; the yellow mule’s ears in the foreground brighten the mood and give this scene an idyllic feeling. Joe was lucky to find clouds in the sky at sunrise—uncommon in the Sierra in summer. But everyone needs a little luck now and then. Technique and vision are important, but there’s no substitute for being in the right place at the right time!

When you find yourself facing a beautiful scene, you have to make the most of the opportunity. The most important consideration is the composition: what, exactly, do you frame?

In the past two critiques (“Red Sky at Night” and “Glen Coe“) I’ve discussed photographs with prominent foregrounds. In both cases I thought the images might have been stronger without them; I felt the backgrounds were more interesting, and the foregrounds distracting.

Here, though, I think the foreground clearly adds to the image; in fact I think the flowers are the most eye-catching thing in the frame. There’s a good visual connection between the bottom and top of the image: the yellows, purples, and greens in the foreground complement the golds, blues, and greens in the background. The arrangement of those flowers also meshes nicely with the peaks: there’s a subtle V shape to the yellow mule’s ears that echoes the broad V of the ridgeline and smaller Vs in the notches between the peaks.

The only minor complaint I have about the composition is that I’d like to see a little more breathing room around the prominent yellow blossoms along the bottom and left edges, and would prefer that the large flower along the left edge wasn’t missing the tips of its petals. Of course zooming out and including more space at the bottom and sides might have introduced other distractions. In a situation like this it’s virtually impossible to avoid cutting some flowers in half, and there could have been patches of dirt or rocks or other unwanted elements that needed to be cropped out of the frame.

So I’m going to give Joe the benefit of the doubt here and assume that there were good reasons for not including more space around the bottom edges. Overall I think he did a good job of finding a foreground that adds something to the photograph, and positioning the camera to emphasize that V shape of the flowers.

But as always, I’d like to hear what you think. Does this foreground work? What do you think of the composition overall?

Technically this is well executed. Joe used a small aperture, f/18, to get sufficient depth of field, and everything looks sharp, even at a larger size. Wind can often be a problem when capturing images like this—you need a small aperture to get depth of field, but that forces you to use a slower shutter speed. Perhaps Joe got lucky (again!) and found a calm morning.

Joe said he used a three-stop graduated neutral-density filter to balance the bright sky with the darker foreground. Mountain scenes like this often require a graduated filter or exposure blending to balance sunlit peaks or sky with shaded areas below. Here the transition looks pretty natural; I don’t see any obvious line that would make the filter’s presence obvious.

Non-HDR Version

Joe told me that he processed the Raw file three ways—normal, one stop under, and one stop over—then merged those three images with Photomatix HDR software. The result appears natural, again, with none of that HDR grunge look. The only hint that this might be HDR is that some of the colors, particularly the yellow-orange flowers, might be slightly over-saturated, and when viewed larger you can see a thin blue halo along the tops of the peaks—although that might be chromatic aberration in the lens (which could be fixed in Lightroom or Adobe Camera Raw), or oversharpening, or both.

Joe said that he also processed the image without HDR, and actually liked that version better, so I asked him to send it to me, and here it is (left). Personally I prefer the HDR version; the shadows are more open, and it feels more luminous. Just for fun I tried to adjust this non-HDR version to look more like the HDR version. I used a little Fill Light in Lightroom to open up the shadows, added Clarity to boost midtone contrast, then increased Vibrance to approximate the saturation in the HDR version.

The result, shown below, is actually pretty close to the HDR photograph, and in some ways I like it better. But it shows that there are many ways to process an image. There are no right or wrong answers—just different interpretations.

Non-HDR version with added Fill Light, Clarity, and Vibrance

Overall this a well-seen, well-executed photograph in which the foreground and background complement each other nicely.

Thanks Joe for sharing your image! You can see more his work on Flickr.

If you like these critiques, share them with a friend! Email this article, or click on one of the buttons below to post it on Facebook or Twitter.

As part of being chosen for this week’s critique Joe will receive a free 16×20 matted print courtesy of the folks at Aspen Creek Photo. If you’d like your images considered for future critiques, just upload them to the Flickr group I created for this purpose. If you’re not a Flickr member yet, joining is free and easy. You’ll have to read and accept the rules for the group before adding images, and please, no more than five photos per person per week. I’ll be posting the next critique in two weeks. Thanks for participating!

by Michael Frye | Jul 27, 2010 | Advanced Techniques, Digital Darkroom, Video Tutorials

Vision is the most important part of photography. Your eye is what makes the difference between a great photograph and a mediocre one.

But when realizing your vision and making it come to life in the final image, getting the right color is vital.

Recently I posted two videos about using curves in Photoshop, Lightroom, and Camera Raw. But there’s a more fundamental step that I haven’t talked about, something you might want to do with Raw files before adding curves, correcting white balance, or doing anything else: choosing a profile.

What is a Camera Profile?

A camera profile is a translator: it’s translates the colors that a camera captures into the colors they should be. In other words, if a certain camera tends to turn reds into orange, the profile will correct for that and convert those reds back to their proper hue. Of course there’s no such thing as “correct” color—it’s all subjective. So profiles can come in different flavors: more saturated, less saturated, more contrasty, etc. Choosing the right flavor for your image is the first step toward making your visualization come to life.

I’ve posted a new video on YouTube that delves into this seemingly esoteric yet actually quite simple subject. In it I show you how to choose different profiles in Lightroom, and explore whether creating a custom profile might be worthwhile. I evaluate some profiles I made with the X-Rite ColorChecker Passport, a $99 package for making custom camera profiles in any lighting situation. Yes, full disclosure, they actually gave this to me for free—I must be hitting the big time!

Also, there’s one more reason for exploring different profile options: reducing noise, banding, and posterization. I show an example where the profile choice made a dramatic difference in noise and banding.

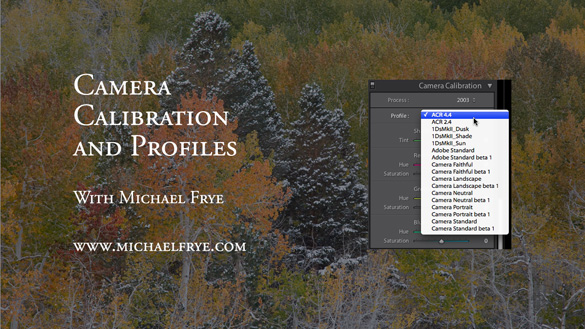

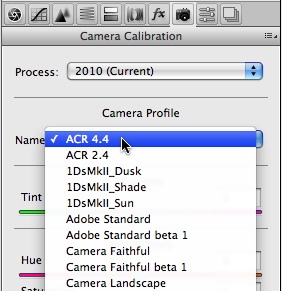

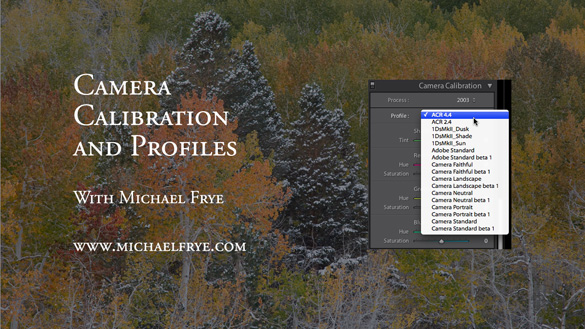

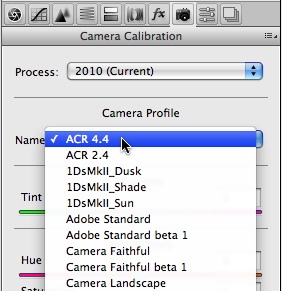

I didn’t have time to demonstrate it in the video, but the same profile choices are also available in Adobe Camera Raw—just look under the Camera Calibration tab, third from the right, as shown here.

So here’s a link to the video:

Camera Calibration and Profiles

As always, it helps to view this at the highest resolution, 480p, and click on the double-sided arrow to make the video larger.

I hope you enjoy it! Comments are always appreciated, and if you like video, please share it with a friend: Email this article, or click on one of the buttons below to post it on Facebook or Twitter.

by Michael Frye | Jul 1, 2010 | Critiques

“Forest Sunrise #1 – Olympic National Park” by Mike Livdahl

This week’s photograph was made by Mike Livdahl in Olympic National Park, Washington. By having his image chosen for this critique Mike will receive a free 16×20 matted print from Aspen Creek Photo. If you’d like your images considered for future critiques you can upload them to the Flickr group I created for this purpose.

The most striking thing about this photograph is the fantastic light, with sunbeams radiating through the mist from behind tall trees. Light is the essence of photography. When we press the shutter we’re not recording objects, we’re capturing light. Often great light is enough to make a great photograph, even if the subject isn’t that interesting. These trees are nice, but without those sunbeams this would be a rather ordinary scene.

The exposure for such strong backlight can be tricky, but Mike handled it well. We see detail in all but the darkest parts of the tree trunks, yet the only the very brightest highlights are blown out. This is one of those rare instances where it’s okay to have some small washed-out areas in the photo, because this is something we would see in real life: looking at this scene the sun and adjacent sky would be blinding, and we wouldn’t expect to see detail in those areas in a photograph.

Mike said that he “exposed hoping to keep some life in the shadows.” As a result, he had to (in Lightroom) “damp the highlights pretty heavily, Recovery pushed to +81 and Brightness dropped to +29.” I guess that’s testimony to how much hidden detail can reside in seemingly overexposed highlights in Raw files. But if I were photographing this scene I’d keep my options open by bracketing exposures, allowing me to blend two or more images together later if necessary.

While the light in this photograph is exceptional, even great light could be ruined by a poor composition. Fortunately it wasn’t. The composition is clean and simple, with a strong focal point, the sunbeams, and some nice repetition created by the lines of the tree trunks. Mike chose a vertical orientation to emphasize the height of the trees. The sunbeams are centered from left to right, a configuration that works well in most vertical compositions (see my post about Sideways Photography).

That vertical orientation, however, with the sunbeams near the bottom of the frame, leaves a lot of space in the top half of the photo. The bottom part of the image is clearly the most eye-catching area, and I always think it’s best to fill the frame with the most interesting stuff. There seems to be a natural horizontal composition here, including only the areas around the sunbeams:

Alternate, horizontal crop

I think this tighter, horizontal framing has more impact, but it doesn’t convey the trees’ height, and loses some sense of place as well. So it’s a tradeoff. Which version do you prefer? Post a comment to share your thoughts on this.

Mike said that he handheld this photograph, leaning against a tree, at 1/15th sec. and 5.6 with an ISO of 400. Since this shutter speed resulted in a slightly soft photo, he added extra sharpening in Lightroom. In a larger view some of the closest branches are a bit soft, indicating that the wide f/5.6 aperture wasn’t enough to keep everything in focus. Obviously a tripod would have been a good idea here—it would have prevented camera movement while allowing a smaller aperture with more depth of field.

The post-processing looks well done; the white balance looks right, and the heavy use of the Recovery tool created a perfect range of contrast—small areas of black, small areas of white, with a full range of tones in between.

Overall this is well done—beautiful light composed well.

Thanks Mike for sharing your image! You can see more his work on Flickr.

If you like these critiques, share them with a friend! Email this article, or click on one of the buttons below to post it on Facebook or Twitter.

As part of being chosen for this week’s critique Mike will receive a free 16×20 matted print courtesy of the folks at Aspen Creek Photo. If you’d like your images considered for future critiques, just upload them to the Flickr group I created for this purpose. If you’re not a Flickr member yet, joining is free and easy. You’ll have to read and accept the rules for the group before adding images, and please, no more than five photos per person per week. I’ll be posting the next critique in two weeks. Thanks for participating!

by Michael Frye | Jun 24, 2010 | Advanced Techniques, Digital Darkroom, Video Tutorials

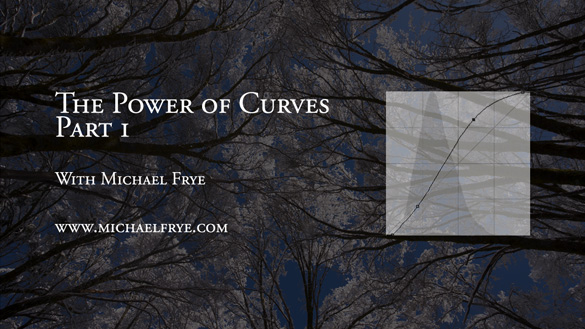

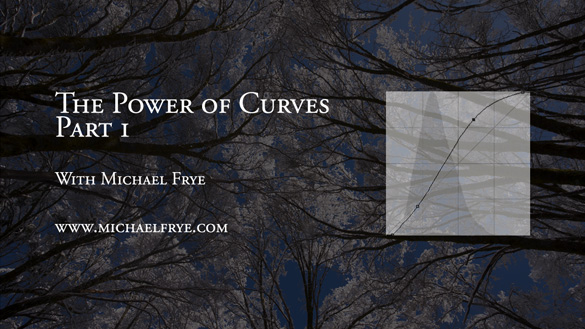

I did something I’ve wanted to do for a long time: post a video tutorial on YouTube. It’s called The Power of Curves, and it’s about, well, curves in Photoshop. This is one of those things that’s just easier to show than explain, so it’s a perfect subject for video.

I think Curves are the single most powerful tool in the digital darkroom; if you learn to master Curves, you’re well on your way to mastering image-processing. Curves tend to intimidate some people, as they seem foreign if you haven’t used them before. But Curves are really quite simple, and I hope this video helps clarify how to use this amazing tool. I had to break this into two parts; here are the links:

The Power of Curves Part 1

The Power of Curves Part 2

Originally I had wanted to talk about the new Point Curve feature in Lightroom 3, but then realized that I needed to explain some basics about Curves first, and that Photoshop was a better tool for that. But I’ll post another video in about two weeks about using Curves in Lightroom and Adobe Camera Raw, and about dealing with their strange default settings.

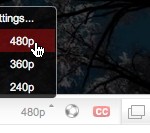

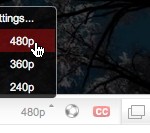

So I hope you enjoy these—let me know what you think! To see everything clearly you need to view in high resolution—click on where it says 240p or 360p in the lower-right corner and choose 480p. Also, if you click on the little double-sided arrow you’ll see the video larger.

So I hope you enjoy these—let me know what you think! To see everything clearly you need to view in high resolution—click on where it says 240p or 360p in the lower-right corner and choose 480p. Also, if you click on the little double-sided arrow you’ll see the video larger.

by Michael Frye | May 27, 2010 | Digital Darkroom

This photograph of Mono Lake, processed entirely in Lightroom, shows the power of modern applications that work directly with Raw images.

There are probably as many workflows as there are photographers. There’s nothing wrong with that: everyone’s different, and a good workflow for one person can seem awkward to another. But sometimes I look at people’s workflows and think the pieces have been gathered from random tips found on the internet, assembled in no particular order, and held together with duct tape and chewing gum.

Just because you’ve always done it one way doesn’t mean that’s the best way. It’s worth periodically examining your practices to see if they still serve you. I do this all the time: I question each step, and ask if there’s a better way to do it. I look at new tools and techniques and see if they could add efficiency, power, or flexibility. I’m constantly refining and improving my workflow, and in the long run this saves me hours of valuable time.

What is a workflow?

Simply put, it’s all the steps you take to process images, including downloading, editing, keywording, developing, and output (printing or uploading images to the web). While you don’t always have to perform each task in the same order every time, it’s helpful to develop a routine so you don’t forget important steps, and don’t need to invent new procedures for each photograph. In this post I’m going to concentrate on the developing part—the operations you perform to optimize an image and make it look its best.

(more…)