Porpoising chinstrap penguins, Antarctica. 355mm, 1/1500 sec at f/16, ISO 5000. I needed a fast shutter speed to freeze motion, and a small aperture to get all the penguins in focus. That required pushing the ISO quite high, but I can deal with the noise (Adobe’s Denoise did a great job), while I can’t fix a blurry photo.

Penguins are so much fun to watch. I need penguins in my life every day. I think everyone does. Luckily I can watch Claudia’s videos whenever I need a penguin fix.

It’s super fun watching penguins at their nests, with the adults performing displays and calls, stealing rocks from neighboring nests, and feeding their adorable chicks. But it’s also highly entertaining to watch them away from their nests – especially as they’re porpoising out of the water, jumping ashore, or leaping into the water en masse.

Penguins are fast and agile swimmers. Gentoo penguins are thought to be the fastest swimmers, reaching speeds of up to 22 mph. (This video shows how fast and agile they are underwater.)

While traveling they frequently jump out of the water – “porpoising,” as it’s called. Porpoising allows them to catch a breath without slowing down (note how their beaks are all open in the photograph above). It may also help them avoid predators, and see over longer distances to navigate.

This porpoising behavior is cool to see in person, but very hard to photograph. Most of the time it’s nearly impossible to predict where they’ll pop up, and by the time you train your lens on them they’ve disappeared back under the water.

Our best opportunity to photograph porpoising penguins came in zodiacs while we hovered offshore from a large chinstrap colony. Groups of one, two, or three dozen penguins were swimming to and from a beach near the colony, porpoising as they went.

So we parked the zodiac along their travel route, looking toward the reflection of a black volcanic cliff, which gave the penguins a nice dark background. We would alert each other as a group approached, then try to follow their path, estimating where they might pop up, and ready to mash down the shutter button when they leapt into the air.

A good percentage of these photos were out of focus, or caught penguins at the edge of the frame, or showed only their feet as they re-entered the water. But a surprising number were actually sharp, with penguins in good positions. Part of that was due simply to the sheer numbers of penguins swimming by, which increased the odds of getting lucky. But we also got lots of practice, which allowed us to better anticipate their movements.

The photo above is my favorite image from that session, and probably my best porpoising penguin photo from our two trips to Antarctica. But it was a challenge!

We also watched groups of penguins leaping into and out of the water along the shore. Aside from southern giant petrels, which I showed in my last post, the main penguin predators on the Antarctic Peninsula are leopard seals. Leopard seals will wait offshore from a penguin colony and try to pick off penguins as they swim in and out. The penguins know this, and join into groups to help evade the seals. A large group of penguins jumping into the water at once, then darting away in different directions, might confuse a leopard seal and make it difficult for the seal to pick out an individual to chase.

We saw this behavior most often with Adélie penguins. Adélies would head down from their nests to the shore, then wait at certain designated spots where they commonly entered or exited the water. When enough penguins had gathered they would all start moving toward the shore, then hesitate. Who wants to go in first? Not me! You go first! Eventually one would dive in, with the others following closely behind. But often some would chicken out and hop back onshore.

This photo shows a group of Adélies jumping into the water. There are twenty penguins visible here, but I can tell by the splashes that at least two more have already entered the water:

You’ll find a few more of my photos of leaping penguins at the bottom of this post. But Claudia also put together a great video of leaping penguins. I could watch this over and over:

We feel so lucky to have spent time with penguins on our two trips to Antarctica. They’re such a treat to watch. I hope we get to go back. But in the meantime, the photos bring back memories, and the videos make me feel like I’m there again.

— Michael Frye

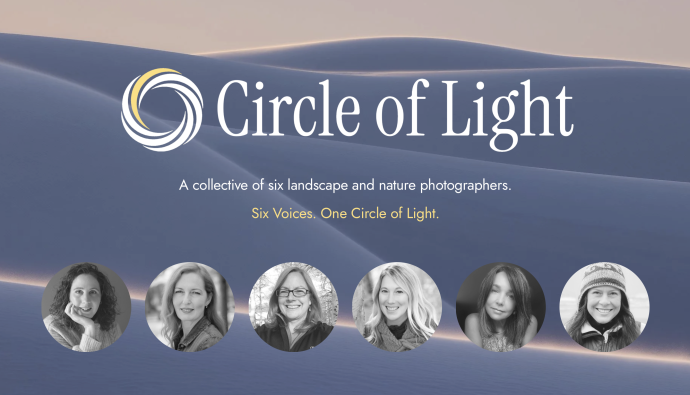

Circle of Light

P.S. Claudia is a wonderfully talented, creative photographer and videographer. She and five other photographers have formed a group called Circle of Light, and they’re poised to launch a new ebook soon. Claudia and I are both really excited about this new venture; here’s what she has to say about joining this group:

I’m pleased to introduce Circle of Light, a photography collective I’ve joined with Charlotte Gibb, Anna Morgan, Jennifer Renwick, Michele Sons, and Sarah Marino.

I’ve been immersed in professional landscape and nature photography for years, but usually as an observer and supporter. Most of what I photograph stays private, just between me, Michael, our cats, a few friends, and the landscapes I visit. But Circle of Light has changed something for me.

I’ve known all of these women for some time and deeply admired their work. What brought us together wasn’t just mutual respect, but ongoing conversations about what truly matters in nature photography – the importance of knowing a place deeply, of returning again and again, of forming authentic relationships with the landscapes we photograph. We wanted to create something personal and meaningful that honored those connections, and it’s those connections that have inspired me to share more of my work in our first group project.

We’re finalizing the design now for our new ebook collaboration, The Nature of Place: Personal Narratives in Landscape Photography, and the excitement is building! We expect to release the ebook in late April 2026, with more details coming this spring.

I’m honored to be part of this circle.

—Claudia Welsh

Learn More About Circle of Light:

And getting back to penguins, here are a few more photos of them leaping:

Related Posts: Life on Ice; Ice Sculptures; Petrels and Penguins

Michael Frye is a professional photographer specializing in landscapes and nature. He lives near Yosemite National Park in California, but travels extensively to photograph natural landscapes in the American West and throughout the world.

Michael uses light, weather, and design to make photographs that capture the mood of the landscape, and convey the beauty, power, and mystery of nature. His work has received numerous awards, including the North American Nature Photography Association’s 2023 award for Fine Art in Nature Photography. Michael’s photographs have appeared in publications around the world, and he’s the author and/or principal photographer of several books, including Digital Landscape Photography: In the Footsteps of Ansel Adams and the Great Masters, and The Photographer’s Guide to Yosemite.

Michael loves to share his knowledge of photography through articles, books, workshops, online courses, and his blog. He’s taught over 200 workshops focused on landscape photography, night photography, digital image processing, and printing.

Outstanding work, as usual. Loved the images and Claudia’s videos are exceptional. Thank you both for sharing